September 26, 2024

Analytical Thinking – Logic Will Only Get You So Far

Analytical thinking is the mental activity that leads us towards making a correct and informed decision. With generative thinking we can come up with tons of ideas for our problem, but we need analytical thinking to help us, sort, screen and select from them to make the transition from idea to solution.

We risk throwing away a good chunk of our most fruitful ideas by analysing them prematurely and this is why we should ‘put off’ analytical thinking until after we’ve generated a sizeable pool of potential solutions to our problem. Once we’ve done this, we can switch from suspending judgement to critical evaluation to whittle down our options and ultimately select the best one to carry through to implementation.

“Get the habit of analysis – analysis will in time enable synthesis to become your habit of mind.”

Frank Lloyd Wright, American architect and writer

A widely held view of this process refers to Divergent-Convergent thinking. When we apply generative thinking we’re ‘diverging’ our thoughts broadly to generate more ideas. With analytical thinking we’re ‘converging’ our thoughts to a single point – the solution. Analytical thinking is therefore a logical follow-on to generative thinking, bringing a healthy dose of reality to the creative process.

Analytical Thinking in Action

The basic challenge for analytical thinking is how to manage and make practical use of the output of creative ideas from the generative thinking stage. How can we filter out the bum ideas without hastily killing off those which could be made to work with a little adjustment? And how can we make positive, objective and explicit judgements on our ideas? These questions are important because it’s the effectiveness of our analytical thinking that determines how well we make use of our creativity.

“Logic is the beginning of wisdom, not the end.”

Leonard Nimoy, American actor and film director

The analytical process typically involves breaking down options and ideas into smaller elements. We then make reasoned assessments about how valid, effective, important, relevant, useful and worthwhile they are in order to arrive at our final solution. All in all analytical thinking follows a methodical and scientific approach to problem solving and decision making. A lot of people believe that analytical thinking and critical thinking are one and the same. For others (including me) critical thinking appears to encompass lots of different strategies of thinking under one banner and, as a result, makes very little sense at all. To me, critical thinking implies bearing down on a problem or issue and picking holes in it i.e. being critical about it. There’s an underlying assumption of unearthing errors, defects or incorrect conclusions. Being critical is a necessary skill – it helps us to reason things out and identify the main contentions in issues, but it needs to be handled properly so our thinking doesn’t become discoloured by invalid reasoning. What people really need for the problem solving process is well-managed analytical thinking. Rather than focusing on finding flaws, we analyse knowledge and possibilities positively to better understand them and come to a sound and workable solution. I recommend the following three guidelines to smoothly facilitate the way you carry out analytical thinking:

1) Narrow down ideas using positive judgement

Immediately after the generative thinking phase, you’re left with a bunch of random ideas that you now need to reduce down to a meaningful quantity before you can conduct a successful analysis. Considering general practicalities, feasibilities and costs will help in eliminating the bulk of ideas to a shortlist of approximately three to six viable contenders.

“Replace ‘either/or’ thinking with ‘plus’ thinking”

Craig R. Hickman, Author of ‘Creating Excellence’ and ‘An Innovator’s Tale’

During this period it’s crucial to remain completely open minded as it’s all too easy to fall back on the safe ideas that you’ve tried before or have heard to work for others. Remember, innovation doesn’t come from the same old ideas; it comes from bold, fresh and novel ideas. Judgements starting with “no, because…” should be avoided. These negative openings discourage discussion by closing the door to further evaluation on an oddball idea that could possibly be made to work if modified in some way. If you begin a judgement with “yes, if…” this invites further speculation on the idea. It gives it a chance to breathe and may eventually materialise a very practical solution that would otherwise have been rejected as being unrealistic.

Researchers at Cornell University found that people with limited knowledge in a certain domain automatically overestimate their ability and performance. Because of this, not only do they reach erroneous conclusions and make unfortunate choices but they fail to realise it. This is a hazard we must all be alert to when thinking analytically. Recognising our limitations helps us become more accurate in our judgements about the ideas that are most meaningful to our problem, and those we should set aside. When working in a group, any idea that has the support or interest of even just one member of the team should stay and those without any backing can be eliminated.

“If a man will begin with certainties, he shall end in doubts. But if he will be content to begin with doubts he shall end in certainties.”

Sir Francis Bacon, British author and philosopher

This stage can be tricky as there’s a delicate balance between eliminating too many or too few alternatives which can impact on later evaluation. Being ruthless and purging all but the ‘best’ options will make the following evaluation stage easier and faster, but it also increases the possibility of getting rid of an option that, when all factors have been counted, might have turned out to be the best choice.

2) Evaluate ideas using appropriate criteria and techniques

How do you decide which ideas are better than others?

Once you’ve whittled down your ideas to a shortlist of three to six possible solutions, it’s time to begin a more precise and systematic analysis. This involves applying evaluation techniques and criteria to determine the worth of your selected ideas. The techniques you can employ at this stage range from simple rating systems (e.g. rating ideas on a scale of 1 to 10) to specialised methods for weighing pros and cons (e.g. Force Field analysis), to full blown measurement systems for complex decisions (e.g. Analytic Hierarchy Process, AHP7).

It’s important to be aware that some rote-step analytical approaches are too demanding and complicated to be effective for what most circumstances demand. Many individuals and groups are put off by highly complex and formal tools as maintaining the discipline to apply them to problems other than the most extreme issues can be difficult. Ideally your methods and criteria should be somewhat broad and flexible, but not too hazy. The key thing is that they keep you organised while in search of the right solution. For instance, UK retail giant Tesco uses the following simple but constructive criteria for approving ideas.

- Is it better? (For customers)

- Is it simpler? (For staff)

- Is it cheaper? (For Tesco)

So the ideas that are better, cheaper and easier are the ones most likely to be taken forward.

“An expert is someone who has succeeded in making decisions and judgements simpler through knowing what to pay attention to and what to ignore.”

Edward de Bono, Author, consultant and inventor of ‘lateral thinking’

3) Choose the best solution(s)

Lastly, having gone through the evaluative process, you’ll end up with one or two viable solutions to carry forward to implementation. Before you make a decision to implement a solution ask yourself:

a) Will the solution achieve what you want?

The solution has to be significantly workable in addressing the problem. It must have the optimal combination of benefits to most successfully resolve the problem, rather than just being ‘good enough’ for now.

b) Is the solution in line with your ultimate goals and objectives (individual or organisational)?

Keeping the big picture in mind is vital to make sure your solution addresses the problem in a comprehensive and integrated way.

c) What are the possibilities it will fail and in what way?

Often the solutions with the greatest potential also carry the greatest risk. You’ll need to consider how much risk you’re willing to take in your particular situation.

Asking these questions expands your analytical thinking and fuses your final decision with objectivity and positive reasoning.

‘Whole Brain’ Analytical Thinking

The general view of analysis is that it’s a predominantly left brain cortical skill. However, recent scientific research is shedding new light on this soon to be outdated supposition. Most people perceive chess to be an entirely analytical sport and science supports this to a point – fMRI scanning shows that amateur chess players typically apply left brain analytical processing to work out a chess problem. But with chess grandmasters, who are quicker in tackling the same problem, the picture is somewhat different. While still engaging similar left brain structures to the amateurs, these expert players also go on to employ additional structures in the other half of their brain.

From this evidence, we can deduce that the difference between being good and being great at something is the ability to use whole brain skills, even during what we might consider ‘left brain’ tasks. Hence, to excel at analytical thinking, you have to be more than just analytical – you have to use additional resources.

An Aid to Creativity…..

What should be clear by now is that analytical thinking is an indispensable part of a well thought out problem solving process. Still, if we were to use it on its own it would be totally insufficient for our needs. Analysis and judgement are great for avoiding the errors of erratic and unrestrained thinking but, as Edward de Bono tells us, they can’t replace the “generative, productive, creative and design aspects of thinking” that are so vital to the problem solving and decision making process.

Traditional analysis is only concerned with what we already know about something, not what we can discover. If we’re going to get the best out of a situation we need to employ generative qualities to explore and source new aspects and outlooks. Although it seems to make sense to eliminate illogical ideas as they come along during the generative phase of thinking, you’re effectively killing off some of your best, most creative ideas from the outset. Despite this, it’s a mistake to view analytical thinking as the death of creativity. Performed properly and at the correct times, analytical thinking can be a brilliant aid to creative thinking. It might be an inefficient and dangerous way to explore new ideas but it’s perfect when you’re trying to decide between different alternatives! Where generative thinking gives birth to ideas, analytical thinking raises and develops solutions.

What many people find surprising is that you can actually be very generative and divergent in your thinking during the analytical phase of the problem solving process. Frankly, this is what will keep your thinking open and inspired and steer you away from the temptation to adopt boring, mediocre ideas simply because they ‘make sense’.

“The ultimate solutions to problems are rational; the process of finding them is not.”

W. J. Gordon, Author of ‘Synectics: The Development of Creative Capacity’

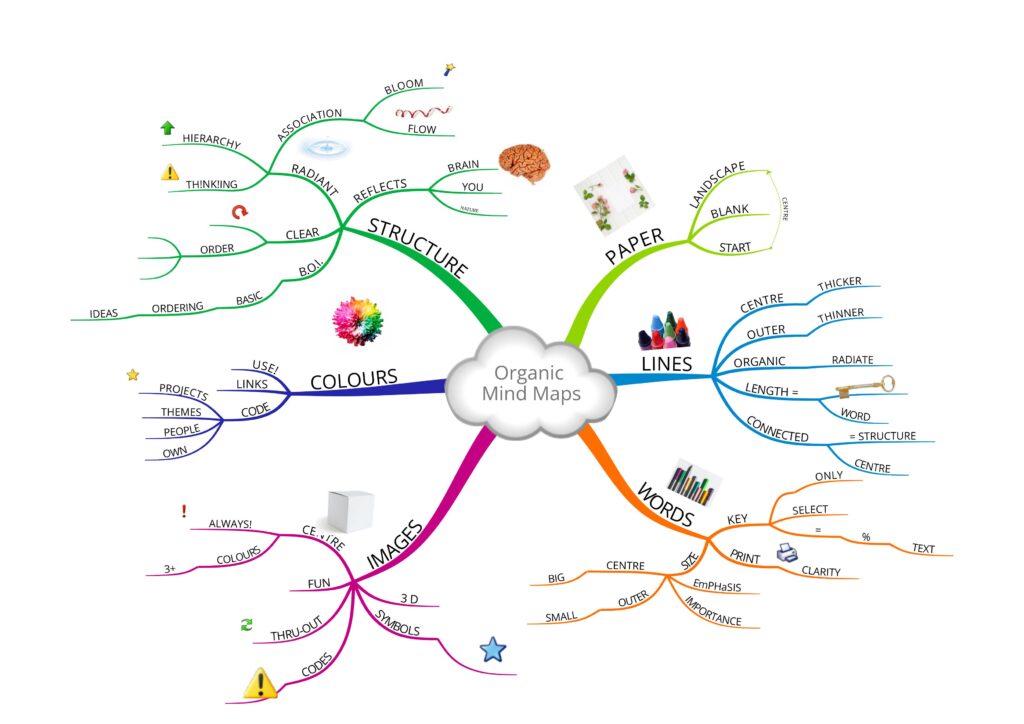

Mind Mapping is clearly a divergent thinking process – we expand outwards from the centre to generate ideas and explore new associations. One of the comments I typically get in relation to Mind Mapping is along the lines of “I really like it but it’s a very generative tool – ideas shoot off in all directions – what I really need is a convergent tool to get to a solution.” What’s worthy of understanding is that a generative thinking tool like the Mind Map can be helpful during both the divergent (generative) AND convergent (analytical) stages of the problem solving process. It can actually assist you in reaching a winning solution much more actively than your bog-standard analytical process. As psychologist J. P. Guilford points out, divergent and convergent modes don’t have to be isolated from each other – they can be merged in so far as a divergent approach can be used on the journey to a convergent solution.

Once you’ve built up a huge pool of ideas during the generative phase of problem solving, you simply use the divergent form and structure of the Mind Map to converge to the most appropriate and useful solution. When you Mind Map, you’re naturally pulled into a generative frame of mind so you can evaluate a limitless number of angles in relation to each possibility. This helps you separate the wheat from the chaff without all the stress that usually comes with this process.

During analysis you break things down into smaller components and this can often mean that you lose sight of the interactions between them, decreasing your comprehension and insight. When this occurs you risk overanalysing things and becoming muddled up. With a Mind Map, you can visually see the ‘big picture’ in addition to all the smaller facts and details – your vision is no longer narrow and you have full control of the situation. This control leads you more directly to your solution than any complex or convoluted process could.

The Mind Mapping process also adds lots of extra vigour to your analytical thinking because you’re able to apply ‘whole brain analysis’. You can tap into a wide range of cortical skills, both rational and imaginative, to evaluate each idea in a more productive and cohesive way. What’s more, your attention is constantly drawn to the heart of the matter (centre of the map) so you remain in an objective and focused frame of mind when selecting a solution. This is critical! You must always stay in tune with your objective when analysing alternatives. While novel and original factors are important for producing a creative solution, when it comes to the crunch your choices and decisions must always apply to the problem. Originality without focus is of little use in the real world.